Listen 來聽

Transistor Radio 原子粒收音機

Continuing Uncle Ho’s Story: From Technician to Engineering Designer

續何叔的故事 – 從技術員到工程設計師

Listen 來聽 / Meanderings - Feature Story 咫尺 - 專題故事 / Feature: Sound Professionals 聲音職人系列

Interview & Editing 採訪、編輯、整理:Law Yuk-mui/ 羅玉梅

English Translation 英譯 : Elaine W. Ho/ 何穎雅11/03/2014

Wan Chai, Hong Kong

Tascam DR 40/ Handheld 手持錄音

cicada, distortion, farmland, LC, production line, radio, ringing, Zhongshan, 中山, 信用狀, 失真, 收音機, 生產線, 耳鳴, 蟬, 農田

(left) Uncle Ho(Ho Hon-chong) at the Hong Kong House of Stories, 2014. (right) Uncle Ho at work, 2006.

(左) 何叔(何漢忠)於藍屋香港故事館,2014年攝。(右)何叔工作時照片, 2006年攝。

The Library: How did you join the profession?

Uncle Ho: I went to night school at the Christian vocational training school in Wong Tai Sin, and studied electronics for about one year, but nobody would hire me. Why? Because I didn’t have any experience, and even if you understand the theory you don’t necessarily understand things on the production line. There was one company that was quite strange though. Everyone there was new; not a single person was technically experienced. So they hired me, and I ended up working there until 2006.

When I started out in the 70s, I entered the industry as a technician in charge of repairs on the production line of the workshop. There were radios that didn’t meet up to standard, or parts that got damaged in the production process, so technicians were needed to make the repairs. In 1975 I started to work as a manager to take charge of one of the production lines. One production line would have 30, at most 60 people working on it. Ten to twelve girls were responsible for assembling parts, each of them taking care of ten plus parts. So for ten people there were 100 pieces assembled. In addition, there were ten other people responsible for mounting the rest of the parts, like the power switch, coils and antenna. After that came the tuning—five to six girls would take care of adjusting the channels. If there were problems, the radio would be transferred over to one of the five or six young men to repair. Each girl had a young man appointed to help her repair the radios with problems, and that was my post when I first entered the trade.

After a while, I was promoted to general manager. At its prime, the company had three factories, one in Macau and two in Hong Kong. I was in charge of managing all three. Later, all the factories moved to the mainland, and in 1981 I started to work in Zhongshan, where I stayed until returning to Hong Kong in 1984. Back in Hong Kong, I was transferred again to another position in charge of buying materials.

The Library: How was the working environment in the mainland at that time?

Uncle Ho: Back then transportation was really inconvenient, and the phones were always out of service. It was practically like being cut off from any communication, and it was very boring. The electricity for our factory was self-generated, so the generator was only turned on during working hours. When you went back to the dorm at night it would be pitch-black. The main thing I heard was the sound of cicadas from the farmland. There were two nights when I was completely unable to sleep, barely holding my eyelids up until dawn.

In 1994, this factory closed down. Though it was still a booming period for the electronics industry, clients were more demanding than before; the price had to be low and the quality high. When it came to payment method, it used to be that the clients would draft an LC—do you know what an LC is? It means ’Letter of Credit‘. The clients would put a sum of money into the bank, and I (as the manufacturer), upon receiving your credit letter, would begin production. The finished goods would be transported to a shipping company over in Kwai Chung. After they arrived at the shipping company, I’d get a bill of lading that could be taken to the bank to withdraw the funds. But the situation started to change in the 1990s. Clients stopped using letters of credit, waiting until the goods were received before transferring payment to manufacturers. This kind of transaction wasn’t necessarily high-risk, but if after the goods arrived the buyer refused the shipment, we would lose on the return shipping costs. Often, this affects the cash flow, so some companies didn’t want to continue.

After that I took more than a month’s break before starting to look for work again. At that time many Hong Kong factories had already moved to the mainland, and the only work left was in engineering design. So I moved into CD player design, and kept working up until I retired in 2006.

We use measuring instruments for the most part when working in design. The client would give us a specifications sheet for reference, and designers would first make sketches, and afterwards, a prototype. Then we plug in the components and check whether or not they meet the client’s standards. If there were no problems, we listen. The first time clients see a prototype, they focus on whether it meets their specifications requirements; only afterwards does listening becomes a factor for discussion. Listening involves checking if the tones are crisp enough. The sound of a speaking voice is deemed not good and unclear if it stutters.. Usually, sounds that pass the data specifications also pass the listening test, but they might fail on the speakers. You test the speakers with your ears, and no matter how good the design of your radio is, if the speakers aren’t good, it isn’t up to standard. The specification sheet includes an item called ‘distortion’ which specifies exactly how much distortion is allowed. Why are Japanese radios so crisp and the ones made in Hong Kong less so, and are merely loud? The problem is that the materials used in Hong Kong radios are utilized to the full, while the ones in Japanese radios don’t. By this I mean the IC (integrated circuit) in the amplifier of the radio. Hong Kong radios run on 2W (watts) electricity, but then the load line exceeds 2W. The larger the load line, the larger the distortion, so the sound becomes uncrisp. On the other hand, 2W Japanese radios actually run on 4-5W integrated circuits, so even when turning the radio to the loudest volume, there is less than 10% distortion. The distortion is how much the sound differs from the original sound (fidelity). So when you buy radios, you have to turn it to the maximum volume and listen to how crisp the sound is before you can tell if it’s worth buying or not.

The Library: What was the selling point of Hong Kong radios?

Uncle Ho: Japanese radios were double the price of Hong Kong radios. There’s no denying that the materials they use are better than ours, and their net costs are probably 10% higher than the Hong Kong manufactured ones. But they could sell for double the price, because they had brand names, advertising, and direct sales to consumers. In our case, clients would tell us the brand and the products we make could only go through importers and wholesale suppliers before they reach consumers.

The Library: Last time when we heard you chatting with students, you said that you were deaf on one side and had ringing in the other ear?

Uncle Ho: The deafness came because I went swimming once and wasn’t careful; my eardrum got busted. I suspect the ringing in my other ear is from work. When I was working with CD players for those ten or so years, I often shut myself in a room to do testing. We had a few CDs that we used for testing, and you know what was on them? They had fingerprints, black spots and scratches on them, and the clients would ask us to test the sound with those CDs before accepting their goods.

The Library: How big were those black spots?

Uncle Ho: About 0.8 to 1.2 millimetres. But working in design, there is no way we could make grade bypassing only 0.8 mm spots. If the client asks to test with 0.8, and you only pass with 0.8, once a problem shows up on the production line, the machine still won’t play the test disc. I probably messed up my ear because I was taking care of this stuff every day. You had to test it to the point that the CD player would be able to play that disc, and sometimes the volume would be turned up to its maximum. If the CD player starts to vibrate when you turn it up to maximum, the vibration would shake the laser head and make the CD skip, so it won’t pass. The Library: How much time did you spend handling this kind of work?

Uncle Ho: It’s hard to say. On average, it would be about three to four days in a month. Usually, we could make a new model in just over a month. This kind of testing procedure followed afterwards.

The Library: How does the ringing in your ear affect your life?

Uncle Ho: I have been visiting the Chinese medicine doctor for about one year, and my ear recovered about 60-70%. During June and July of the year before last, my ear would start hearing sounds every evening around seven or eight o’clock. The sound would gradually get louder and louder, so much so that I couldn’t get to sleep. It sounded like cicadas, or something like air being let out of a balloon. The Library: And how has your life been since retirement?

Uncle Ho: At first I was completely happy. But now I start to feel bored. It was great in the beginning because it had been several decades of continuously going to work, get-ting off work, having only weekends off and not being able to really go anywhere in just those two days’ time. Since retiring I can travel everywhere—go to the mainland, Taiwan or Singapore. I’ve been to all of those places by now, but going further away is just too expensive.

The Library: You still look very young.

Uncle Ho: I’m 65. I was about 57, 58 when I retired. Even if you don’t want to retire, you can’t find any more work unless you’re willing to live in the mainland long-term.

The Library: You’ve worked in this industry for several decades. Is there any security for you after you retired?

Uncle Ho: There was a little bit of pension money, but I rely mostly upon my own savings.

[1] An amplifier is used to take a weak signal from the sound source and amplify it, pushing it through the speakers in order to release the sound.

聲音圖書館: 你是如何入行的 ?

何叔: 我是在黃大仙的基督教職業訓練學校上夜校,學了差不多一年的電子,但都沒人請。為什麼呢? 因為沒有經驗,你懂得理論,但生產線的東西你不一定懂。唯獨一間公司很奇怪,全部起用新人,沒有一個是熟手技工,他們聘請了我,我便一直工作到二零零六年。 我七零年入行是做「技術員」的,在生產線工場負責維修。收音機的生產過程會有未達到要求、指標或零件損壞的情況,所以需要技術員維修。七五年我開始做「管理」,那就是管理一條生產線,一條生產線最多有六十人,或者三十多人。十至十二個女孩負責將零件裝上,每人負責十幾顆零件,十個人便一百顆。另外有十個人負責裝嵌其餘零件,包括開關、線圈和天線 。接著是「較機」,五至六女孩負責調台,有問題便交給另外五至六個男孩維修,每個女孩都有一個男孩專門幫她維修有問題的收音機,我初入行就是擔當這崗位。

之後我晉升為總管,在全盛時期公司有三家工廠,澳門一間,香港兩間,我負責三家廠的管理工作。後來全部工廠遷往大陸,我八一年開始在中山工作,直至八四年返回香港後又轉去另一個崗位,負責採購買料。

聲音圖書館: 當時內地的工作環境如何?

何叔:當時的交通非常不便,電話又接不通,好像是音訊全無,而且很悶。我們的工廠的電力是自供的,開工才發電,你夜晚回到宿舍是黑漆漆一片。主要是聽到農田傳來的蟬聲,曾經有兩個夜晚我完全不能入睡,撐著雙眼直到天光。

最後這間工廠在九四年結業,那時候尚且是電子業的全盛時期,但客人的要求相較以前高,價格低之餘又要高質量。特別是付款形式,以前客人開一張LC,你知道什麼叫「LC」? 是「信用狀」。客人會將一筆款項存入銀行,而我(生產商)收到你信用狀就會開始生產,做好的貨物要運送到葵涌那邊的船公司。到了船公司後,拿一張提單便可以到銀行取款。但九十年代情況開始轉變,客人開始不用信用狀,等到貨物運抵當地,再滙款給廠商。這種貿易形式並不是特別高風險,只是如果貨物運到當地,買家不要貨,可以會虧蝕回程的運費,而那筆運費又無法周轉,所以有些公司不想經營下去。

公司結業後,我休息了一個多月再找工作,那時候香港的工廠都已經搬上內地,剩餘下來的只有工程設計。我轉職做CD播放機工程設計直至到零六年退休。 我們做設計的首先是要通過儀器,客人會給我們一份數據指標作參考,設計師先畫圖,然後做樣版,自己插件,測試是否乎合客人的指標,沒有問題再用耳朵去聽。因為客人第一次看樣板,主要看能否通過數據指標,之後談耳朵。耳朵的部份主要是聽音色清晰與否,如果人說話的聲音卡住、卡住,聲音就不好、不清晰。通常能通過指標的,都能通過耳朵,最後不能通過的是喇叭。喇叭必定是用耳朵去聽,無論你設計的收音機做到多好,喇叭不好便不合格。參考標作有一項叫失真(distortion)的東西,就是容許有多大的失實率。為什麼日本的收音機會如此清晰?而香港做的沒那麼清晰,只有大聲兩隻字?問題是日本收音機所用的材料是未用盡的,香港就用到盡。「用到盡」的意思是收音機功放[1]部份那顆IC (integrated circuits/ 積體電路) ,香港人是用到盡,寫出來是兩個W (WATT/ 瓦特), 但其實是超過兩個W,誇大了有什麼壞處? 就是失真,聽起來不清晰。相反,日本兩個W的收音機是用四至五個W的IC,所以就算把收音機調較到最大聲,失真率都在十個百分比以下,失真就是你聽出來的聲音與原來的聲音不一樣。所以買收音機一定要將音量調到最大而覺得清晰才值得買。

聲音圖書館: 香港的收音機的賣點是什麼?

何叔:日本的收音機比香港製造的貴一倍,他們的用料無可否認比我們好,大概比香港製造的貴十個百份比左右,但他們可以賣貴一倍,因為他們有牌子、有廣告,並直接到達消費者手中。相反我們是客人給牌子我們去生產,我們生產的東西只能通過入口商、批發商,再去傳到消費者手中。

聲音圖書館: 上次聽你跟學生聊天,你說自己一隻耳穿了,而另一隻耳有耳鳴?

何叔:穿了是因為游泳時不小心弄穿,耳鳴我懷疑是職業的問題,那十幾年做CD播放機,經常把自己困在房間裡做測試。我們有一些做測試的CD,裡面有什麼呢?有手指紋、有些黑點和刮痕,客戶要求通過那隻CD的測試才收貨。 聲音圖書館: 那些黑點有多大? 何叔:大概0.8 毫米至1.2毫米,但我們做設計的不可能做到僅僅通過0.8毫米;如果客人的要求是0.8,而你只做到0.8,當生產線那邊出現了誤差就讀不到那隻碟,我可能因為每天處理這些東西而搞壞了耳朵。有時候測機還需要將CD播放機音量調控到最大聲,當你調細音量時CD播放機可以讀到那隻碟,但如果調到最大音量時CD播放機身會產生震動,震動時如果雷射頭追不到那一點便會跳線,即是不合格。

聲音圖書館:有多長時間需要處理這些工作? 何叔: 很難說,平均一個月有三至四日。一般而言,我們一個多月便能做好一款新機,最後的工序都會做這類型的測試。

聲音圖書館: 耳鳴對你生活有什麼影響?

何叔:我看了大概一年的中醫,康復了六到七成。前年的六、七月,每到夜晚七、八時耳朵便開始聽到聲音,而且漸漸地大聲,令你不能入睡,那種聲音像蟬叫、又像洩氣的氣球。

聲音圖書館: 那你退休生活如何?

何叔: 起初十分開心,不過現在開始覺得悶。開心是因為幾十年以來一直上班下班,周末放假一兩天也不能去什麼地方。退休後可以四處旅遊,去大陸、台灣或者星加坡,現在那些地方都差不多去過了,去遠的地方價錢又貴。

聲音圖書館: 你看起來還很年輕。

何叔: 我65歲了,退休時大約57、58歲,你找不到工作不想退休也不行,除非你願意長駐大陸。

聲音圖書館: 你做了這一行幾十年,退休後有沒有得到什麼保障?

何叔: 有些少許強積金,但主要靠自己積蓄。

[1]功放的作用就是把來自音源或前級放大器的弱信號放大,推動音箱放聲。

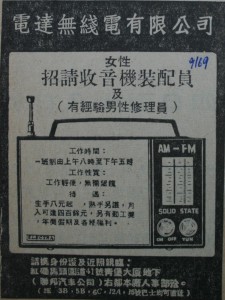

1969 advertisement: “Wireless electronics school with special training for electronics technicians. $15 tuition and you’ll be finished in three months, a value-for-money course!” [Image/text courtesy of the Facebook page of Wu Hou (Old Bifocals)]

「1969年廣告, 出現無綫電學校, 專訓練電器技工, 學費15元, 三個月搞掂, 扺讀 !」(圖片/文字來源: 吳昊(老花鏡) 臉書專頁)

“The economics department of the University of Illinois in the United States issues a survey: In 1968, Hong Kong citizens earned an average of Hong Kong $3,570 per year, approximating $300 per month, second only to Japan for the highest salary in Asia. Women are preferred as transistor radio workers, earning $400 a month!” [Image/text courtesy of the Facebook page of Wu Hou (Old Bifocals)]

「美國伊利諾大學經濟系發表調查 : 1968年港人平均收入每年3570港元, 每月入息約為300元, 僅次於日本, 全亞洲第二高薪。原子粒收音機女工更吃香, 月薪高逹 400元 !」 (圖片/文字來源: 吳昊(老花鏡) 臉書專頁)