Listen 來聽

Interview 採訪:Law Yuk-mui/ 羅玉梅

Editing 編輯、整理:Law Yuk-mui/ 羅玉梅

English Translation 英譯 : Winnie Chau/ 周潁榆

Transcription 謄錄: Janie Chan Tsang/ 陳錚02/27/2015

Hong Kong/ 香港

DJ mix, Japan, tweeting, 日本, 發帖

The musical work of Takuro Mizuta Lippit (aka dj sniff) builds upon a distinct practice that combines DJ-ing, instrument design and free improvisation. He is interested in how a mediated musical memory, from archival collections of vinyl records to digitally captured sound events during a performance, can be used to create a new sonic reality that emerges through the fleeting notion of the “now”.

http://www.djsniff.com/

The Library: Regarding the field recordings of “Umbrella Movement” you shared on SoundCloud. Is it your first time to do field recording in a social movement or protest?

Takuro Mizuta: No, this is not the first time I recorded a protest. The first recording I made was in 2003. I was living in New York at the time and it was when the U.S. was about to invade Iraq. There were many protests against George W. Bush sending troops to the region.

The Library: What was your intention to do field recording in such a kind of occasion?

Takuro Mizuta: I think the main reason was to document the moment, but also to give me a little distance from the situation and things that were happening around me. For me, one contribution I can make to any movement that I participate in is to document, and because there are so many visual documentations these days, I find it more unique to have sonic documentation. I also often use these recordings in my own music.

For example, around the same time in New York, there was a protest against a radio station that made a segment mocking South Asian tsunami victims. I became associated with the group who organized a rally and a boycott campaign. I recorded the sounds and speeches from the rally and made a DJ mix which was later broadcasted.

The Library: Is it an underground radio station?

Takuro Mizuta: The protest was against a mainstream commercial radio station and my work was broadcasted on the Internet, on a website.

The Library: Do you mean “digital radio”?

Takuro Mizuta: Yes, digital radio.

The Library: Talking about the recordings of Umbrella Movement, the first recording you made was on 29 September at 2am, right?

Takuro Mizuta: Yes, on the first day, when the police shot tear gas, I was watching it unfold online, and waiting for the right time to join the protests. That night my wife and I took turns going out, because we have a small baby. She first went to Admiralty and came back to tell me the situation. I went out later that night to Causeway Bay where the situation was very unclear to everyone. Rumors were spreading that the police were advancing east through Wan Chai using tear gas and pepper spray.

Standoff with Police

02:00 AM, 09/29/2014, Causeway Bay

(Please note that the contents contain language that may be offensive.)

The Library: When you are recording, what was your gesture? Did you follow the crowd?

Takuro Mizuta: I had my binaural microphones in my ears and I was walking through the crowd trying to capture their conversations. Some people were building barricades and others were collecting supplies such as water and food. This was before things became more organized as we saw in the following days. Some were telling people to gather, some were telling people to leave. So basically I was trying to move between these groups as much as possible. When I arrived at the frontline, the situation was very tense. The police in riot gear came to confront us and I was there trying to document but also trying not to get hurt.

When I record, I am also very conscious of what not to record because having too much material makes it hard for me to revisit it. The shorter the material the more concentrated I can be when I listen back. So I try to do a sort of “in-recorder edit” thinking about when to hit record. Sometimes I have the recorder on the whole time, but also I have it off a lot. When I see or think something will happen, I just turn it on and go there.

The Library: How do you decide whether or not to record?

Takuro Mizuta: When I was in Admiralty, the sounds were mostly just the general ambience of people’s presence. It was very nice because urban sounds are usually filled with activities by man-made machines like traffic, construction, air conditioners or planes. In this recording, there was none of these. But at the same time there are no sounds of birds or water that would suggest nature. It is a distinctly urban setting because we hear the voices bounce off the concrete structures, and there are thousands of people there. This was really interesting for me.

Peaceful Gathering

11:30 PM,10/01/2014, Admiralty

However in terms of sound events, there was occasional cheering and laughter but most of the time people were just kind of hanging out. There is a lot of dead time in the recording. I often returned to the occupy sites at Admiralty and Causeway Bay but didn’t record anymore because as sound material there was not that much happening.

The Library: Is the version you shared online the exact duration you recorded, or did you make some editing?

Takuro Mizuta: The sounds I put online are actually short excerpts of longer recordings. The original recordings are about 30 to 40 minutes. I had the intention to try to highlight the events, and share the atmosphere of the movement with a wider range of people.

In Japan, people were very interested in the movement. At the beginning, there were only a few people reporting the situation in Japanese and I was one of them. Especially when I was in Mongkok during the confrontation between the protesters and the thuggish anti occupy groups, I was recording and live tweeting on the spot, and many people were following this in Japan. You know, Japan and China have a really sensitive relationship, so people are generally interested in what happens politically. Also, there has been a lot of activism in Japan after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima. Much of this has shifted towards protesting against the current right-wing government and the prime minister. Many of these people closely followed the Sunflower Student Movement in Taiwan, and it was the same during the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong.

Protesters’ Gathering after attacked by Pro-China Thugs

07:30 PM, 10/03/2014, Mong Kok

It is an interesting time in Japan. When I was a student, there was no activism. There was no sort of social movement. There were only small groups leftover from the 60’s that were protesting. This has changed drastically. Now the protests are organized by all generations, and especially the younger people are becoming more active. There are large movements organized by just university students. I think it is a global phenomenon, right? It’s a shared sense of resistance and solidarity to fight against injustice and protect freedom. Recently we‘ve seen large protests in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and in Turkey. For the Japanese people it especially has a strong impact when it happens in nearby places like Taiwan and Hong Kong. As Asians, we feel a stronger sense of sympathy and unity.

The Library: So Soundcloud is the only platform you used to share your recordings?

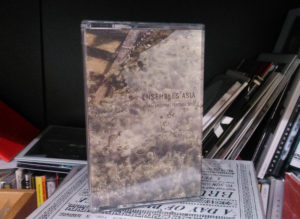

Takuro Mizuta: That’s the main one. I also included some of it in a mixtape that I recently made for a festival in Tokyo called Asian Meeting Festival. This is a five-year project that brings together South East Asian artists with Japanese artists. The mixtape was given to people who came to the event. I used some parts as transitions between tracks, and I also use some during my concerts. I approach the material more on a sonic level rather than addressing the actual content. It fills in for a specific feeling or texture that I am looking for when I am composing or playing live.

The Library: I have a final question. Maybe it is a big question, but I just want to hear your opinion. As an artist, what does this recording means to you? How do you think of the relationship between sound and politics?

Takuro Mizuta: Well, the whole experience was intense, unique, and also very emotional for me. Even as a foreigner, it was very touching to be part of such movement and also see my students get involved. At the same time it was emotionally and physically draining. Now when I listen to the recordings, they remind me how intense it was at the beginning with all the uncertainties. I had forgotten how it felt because after the first month there was a long dragged-out period, and the movement got smaller and smaller. When I listen back, they are like pictures that bring back strong memories.

And the relationship between sound and politics? Um…I mean, to be blunt, there is no relationship whatsoever. Sound is sound and politics is politics. I believe that art and sound or music can’t do anything politically. If you want to make a political statement, or make a change, you shouldn’t trick yourself by saying “I am going make art to do so.” You should go out and do political things. You should organize and rally on the street. You should vote or go talk to your representatives. I think it’s dangerous when people get a false feeling that they are making a change through just an artwork or a piece of music. However, of course, we need art and culture to live. It gives us distance from our daily strife or perspective on things that we were not aware of. But this is different from being political, right? So I have a pretty strong stance that I don’t want to say the sounds I recorded are political. They are what they are – just sounds from a unique situation. We can talk about these recordings in different contexts, and of course in relationship to politics. But it is not my intention to go out and record for these purposes. I am there to participate, document, and maybe find useful sound material for my own future work.

聲音圖書館: 你在SoundCloud上分享的「雨傘運動」田野錄音,是你第一次在社會運動或抗爭場景中錄音嗎?

水田拓郎:這不是第一次。我第一次做這樣的錄音是在2003年,當時我住在紐約,正值美國剛開始入侵伊拉克的時候,有很多反對布殊派兵攻打伊拉克的示威。

聲音圖書館: 甚麼原因驅使你在這些場合進行錄音?

水田拓郎:我想主要的原因是去記錄當下,而錄音同時可以讓我與身邊所發生的事情保持一點距離。對我來說,錄音是我對所參與的運動的一種貢獻 。現在已經有很多視覺上的紀錄,我覺得聲音紀錄是比較獨特的,而且我經常在我自己的音樂中使用這些錄音。

例如,我在紐約時,當時就有一場示威在抗議某電台在節目中拿南亞海嘯遇難者來開玩笑。其後我開始與那個組織集會和杯葛行動的團體有聯繫,我記錄了他們集會的聲音和發言,並製作成唱片騎師混音版本在電台上廣播。

聲音圖書館: 那個是地下電台嗎?

水田拓郎:那次抗議就是在反對主流的商業電台,而我的作品是在互聯網站播放的。

聲音圖書館: 你是指「數碼電台」?

水田拓郎:對,數碼電台。

聲音圖書館: 說回你在雨傘運動的錄音,第一條的聲帶是在9月29日凌晨2時錄的?

水田拓郎:是的,第一天,當警方釋放催淚彈時,我正在網上觀看未經刪剪的片段,並等待適當的時機參與抗議。因為我家有一個嬰兒要照顧,我便與妻子輪流出去。她先去了金鐘,然後回來告訴我那裡的情況。稍晚後我去了銅鑼灣,當時並沒有人知道事態的發展會如何,而有謠傳說警方正經灣仔,往東面方向釋放催淚彈和胡椒噴霧。

與警察對峙

02:00 AM, 09/29/2014, 銅鑼灣

(內容含有粗言穢語,敬請注意。)

聲音圖書館: 你錄音時的動作是怎樣的?你是跟著人群一起走嗎?

水田拓郎:錄音時,我戴著耳道型麥克風,在人群中穿梭,並嘗試錄下他們的對話。有些人在建路障,有些人在收集水和食物等物資,這些都是在事情變得有條理前發生的。有些人在集合群衆,也有些人嚷著叫人離開。所以基本上,我是盡量在這些人群之間不斷移動。當我到達前線時,我覺察到那緊張的氣氛。武裝警察面走過來和我們對峙,而我只好嘗試繼續記錄,但盡量避免受傷。

當我錄音時,我是很有意識地選擇甚麼不要錄,因為過量的資料會令我難以重新查閱它們。資料越短,重聽時我越能夠專注其中。所以,在我按下錄音鍵前,我會嘗試思考如何在錄音過程中進行剪接。有時我會讓錄音機長期處於「開機」狀態,但我亦很常「關機」。當我看見或覺得一些事情將要發生,我會開機,並且走去那裡。

聲音圖書館: 你如何決定錄不錄音?

水田拓郎:我在金鐘時,那些聲音主要是人們在場的大環境聲音。這些聲音很不錯,因為城市的聲音一般都充滿著人造的機械聲音,例如交通、建設、空調或飛機等;而這段錄音裡便完全沒有以上的聲音,同時沒有任何指涉自然的鳥聲和水聲。它顯然是一個城市場景,因為我們可以聽到石屎建築物的回彈的聲音,而且有千人在聚集,這對我來說是十分有趣的。

和平集會

11:30 PM,10/01/2014, 金鐘

然而,就聲音事件而言,當中偶爾會有一些人們的歡呼與笑聲,但絕大部分的時間只是人們在聚集,因此錄音中有不少空白位。我經常重返金鐘和銅鑼灣的佔領區,但我沒有再錄些什麼,因為作為一種聲音的材料,那並沒有什麼特別在發生。

聲音圖書館: 你在網上分享的版本是原來長度的錄音,還是經過剪輯的?

水田拓郎:我放在網上的錄音其實是很短很濃縮的部分。原來的錄音大概爲30至40分鐘。我嘗試去做的是突出這件事,將運動的氛圍向更廣大的群眾分享。

在日本有很多人關心雨傘運動,開始時只有少數人用日文報告香港的情況,而我就是其中的一份子。特別是我在旺角,抗爭者與反佔中一幫人對峙的時候,我在錄音,並即時在網上發帖,當時帖子就受到很多在日人士的關注。要知道中日關係是十分敏感的,人們普遍關切政治上的動向; 加上發生福島核災難後,日本多了很多激進主義的思想,而大多都把茅頭指向現任的右翼政府和首相。在台灣發生「太陽花學運」時,這一幫人緊貼著事態發展,而當雨傘運動在香港爆發,他們同樣地關切。

抗爭者被親中暴徒襲擊後聚集

07:30 PM, 10/03/2014, 旺角

日本現正處於一個有趣的時刻。當我還是學生時,根本沒有什麼激進主義和社會運動,只有少數從60年代走過來的人仍然參與示威,但這個情況經已徹底改變。現在的抗爭是由所有世代的人去組織,年輕人尤其積極;有很多大型社會運動都只是由大學生籌劃的。我認為這是一個全球現象,你説是不是?它是一種共同的反抗意識,一種爭取公義、捍衛自由的團結精神。最近在墨西哥、阿根廷、巴西和土耳其也有大型的示威運動,但於日本人而言,在鄰近國家,比如台灣和香港所發生的事更具影響,作為亞洲人,我們更感到同情和團結。

聲音圖書館: SoundCloud是唯一一個你用來分享錄音的平台嗎?

水田拓郎:它是主要的一個。我亦有將部分錄音加入一個混音聲帶內,這聲帶是我最近的創作,用於東京舉行的 “Asian Meeting Festival”。它是一個連繫東南亞和日本藝術家的五年項目,這混音聲帶是送給來看演出的觀眾。有些錄音我用了來做聲帶之間的過渡,也有一些直接用於我的演出。我是從聲音的層面去使用這些材料而多於它所指涉的內容。當我編曲或作現場表演時,它注入了我想要的感覺和質感。

聲音圖書館: 我有最後一個問題,這可能是一個很闊的問題,但我想聽你的意見。作為藝術家,這些錄音於你的意義是什麼?你如何看待聲音和政治之間的關係?

水田拓郎:對我來說整個運動是十分緊張、獨特和激動的。作為一個外國人,能夠置身其當中,並看見我的學生積極參與是很感動的。與此同時,它是對情感和精力的一種消耗。現在當我聽回那些聲帶,它都喚起我在運動初始時的緊張和不知所措。我都幾乎忘記了那種感覺,因為運動開始後的一個月,有一段很長的滯後期,整個運動規模在逐漸縮小。當我聽回錄音,它就像一幅帶有強烈記憶的圖畫。

至於聲音和政治之間的關係?坦白說,我覺得兩者並無任何關係。聲音是聲音,政治是政治。我相信藝術、聲音或音樂不能做什麼政治化的東西。如果你想提出政治立場或作出改變,你不應該欺騙自己說:「我在做藝術」。你應該走出去搞政治,去組織和參與抗爭,去投票或者跟你的代表對話。我認為那些假想自己可以透過作品或音樂去作出改變的人是危險的。當然我們的生活需要藝術和文化,它讓我們遠離日常的紛擾,透視我們平日不在意的東西,但這跟政治是不同的,對不對? 因此我不想說我的錄音就是政治,它就是在特定場景的聲音而已。我們可以從不同領域去討論這些錄音,包括它與政治的關係,但這不是我走出去錄音的目的。我是去參與、去記錄又或者為未來的作品尋找有用的材料。

Mixtape for “Asian Meeting Festival”/ “Asian Meeting Festival” 混音聲帶